|

|

|

Tuna Fishing In Portugal

Portugal’s great fishing heritage hasn’t entirely been forgotten. Before the race to achieve full EU membership, Portugal was a lot poorer. In the 1950's the town of Vila Real de Santo António, located on the eastern Algarve, was home to over fifty Atlantic Bluefin tuna and sardine processing factories, which were represented by the influential Tuna Exchange that set prices for the rest of Europe. Schools of tuna, migrating into the Mediterranean Sea to breed near Majorca and in the Black Sea, attracted the town’s commercial interests. The Algarve was only the region in Portugal where wall nets were used. In the second half of the 19th century Italian, Spanish and Greek immigrants opened canning factories, from Tavira to Lagos, and by 1890 the Royal Fisheries Company was established. Some even say that the world’s first tinned tuna came from here. Up to 20’000 tuna were caught annually at this time. The golden age of commercial tuna fishing, on the Algarve continued until the 1930’s. At the beginning of the 1930’s the Parodi tuna processing plant in Vila Real Santo António employed modern technology to process up to 1000 tuna daily. Profits from tuna fishing were enormous even if catches were down on the previous century. Decline in traditional fishing activities is due both to the diminishing number of tuna caused by pollution and intensive fishing, and the market laws that have made this fishing technique too costly. Just two canneries remain today, including the Conservas Damasco factory - the tuna boom was over. Fishermen can still be seen pushing out their boats after dusk but today most inhabitants fish for pleasure. Descendents of the foreign entrepreneurs, who established tuna fishing companies along the Algarve, can be found in the phone book, for instance under family names of Feu and Ramirez. From late May, when water temperature exceeds fourteen centigrade, shoals of huge tuna begin their annual migration from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar, before spending one month breeding in the warmer Mediterranean waters.

About fifty fishermen operate a single wall net installation. They drop thousands of red marker buoys, attached to nets, which bob for nearly 2km along the water's surface, anchored by hundreds of weights and forming rows as neat as traffic lanes on a highway. Then they manoeuvre their boats to form a wide square, and they wait. As the sun rises a drama begins to unfold. Nearly two hundred huge tuna glide through the lanes of nets until they find themselves trapped atop a net that the fishermen have connected between their boats. From below, the tuna, which are very wary, see a medieval corridor, shiny nets waterproofed with tar that guides them through a channel leading to a trap.

As the sun rises… The tuna thrash about wildly in a desperate search for escape, but the captains have already edged their vessels into a far tighter square, sealing off all exits. Colossal nets are hoisted by hand. One by one, the exhausted fish die, their bodies banging against the boats, and their blood turns the water red. ….giant tuna, two metres long are hauled onboard

Small boats called enviados landed the fish and manual labourers called tarefeiras cut them up and marinated the fish chunks in pickling brine to conserve them. Then they were placed inside huge underground tanks, previously used as water tanks. They gave off toxic vapours that sometimes killed workers. The product was eventually packed in barrels and exported to Spain and Italy where the company owners had connections. Although this very old fishing tradition and the revenues accruing from some locations continued to be profitable, it’s certain that, at the beginning of the 20th century, the number of wall net installations reduced significantly along the Algarve coast. A gradual decline, in tuna stocks, occurring from the 1880’s until 1924 – when they rose again, had forced the merger of some wall fishing operations. In 1899 armação do Ramalhete (wall fishing operation) was merged with Cabo de Santa Maria Maria Company under one processing facility. In that year the former caught 2’606 tuna, in 1918 it caught just 39 fish, and in 1927 it caught 5’429 tuna. The latter caught 4’358 tuna in 1889, only 127 fish in 1918 and 4’827 tuna in 1907. The last great surge in demand came from the armies in Flanders during the First World War. The most productive fishing area was on the lee-side of the Algarve. Here fishing was restricted to six wall net fishing operations. Concessions were divided between Cabo de Santa Maria and Quarteira and the remaining four between Barra da Fuzeta and Monte Gordo.

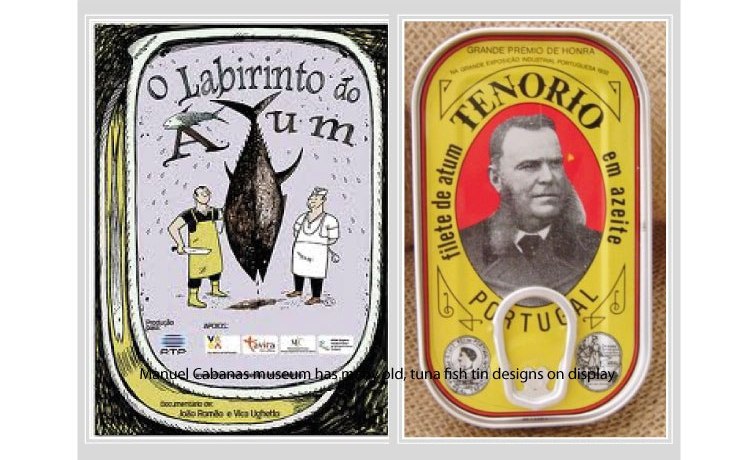

Fishermen load up with tuna, caught off Santo António, 1930’s More than three hundred men were employed on these six wall net operations and their activities were divided into two parts. The pesca de direito (fishing rights) took place from 1st May until 30th June, and were designed to catch fish approaching the Gibraltar straights from the Atlantic Ocean. The Cabo de Santa Maria and Quarteira wall fishing operations stopped after this time. The remaining four, wall fishing operations continued, from 1st July until 31st August to pesca de revés (returning fish), capturing tuna returning to the Atlantic Ocean after spawning. Tavira has a museum dedicated to the history of her fishing industry. Hotel Vila Galé, Albacora Arraial Ferreira Neto, Tavira 8800 – 901. Tel: +351 281 380 800. The Manuel Cabanas museum, which is a small building attached to the town hall (sign posted "camara municipal"). The Rota do Atum tuna festival, takes place every July in Vila Real Santo António. Like to learn more? The Essential Guide to Fishing in Portugal can be sampled here |

|